Black Lives Matter movement comes to France. But will it translate?

BEAUMONT-SUR-OISE, France — His name was Adama Traoré, a 24-year-old black construction worker who loved soccer and spent the summer aching for the much-anticipated French victory in the Euro 2016 finals that never came.

For Adama, what did come this summer was death in police custody on July 19, his birthday. According to police documents shared with select French media outlets, Adama and his brother, Bagui, were stopped on their bikes that afternoon in the center of this small town, which is about an hour north of Paris. The police were after Bagui, wanted in connection with an extortion case.

But when Adama fled the scene, three officers ultimately subdued him by pouncing on his back all at once. By the time they arrived at the station, the officers said Adama was not breathing. He was immediately pronounced dead, but his older brother, Lassana, said in an interview that Beaumont police then told the family they could bring their brother a sandwich while he was held.

The Traorés brought the sandwich to the station, recalled Lassana, 39, a real estate agent, in a cafe near the family’s home. It was nearly five hours after Adama’s arrest before they learned the truth, when, as Lassana said, the authorities first blamed the death of the recreational athlete on a cardiac condition, then on a serious infection. An independent autopsy the family later commissioned suggested the cause of death was asphyxiation.

For several hours, Lassana said, Adama’s “body was in the courtyard of the police station, in the parking lot, on the ground — like a dead dog.”

If that image might seem to some as tragically commonplace in the United States in 2016 — where, according to data collected by The Washington Post, 573 people have already been killed by police this year, nearly 40 percent of them people of color — in France, it has caused some to question the way the country sees itself.

In the weeks since July 19, the question of how Adama died has turned attention on police brutality and structural racism in a proudly egalitarian society that considers itself so institutionally color-blind that it refuses — per a 1978 law — even to collect data on race or ethnicity in annual censuses or government-sponsored research.

To the French state, race — as a quantifiable category but also a separate social experience — is not supposed to exist. In 2013, for instance, the country’s National Assembly passed a bill that would have completely removed the word “race” from the country’s constitution. The bill never became law, but its essence remained: in France, there are no distinct races, only equal citizens.

The case of Adama Traoré is not the first to call into question this long-held ideology of national identity and to suggest that race, perhaps, has mattered all along. In 2005, for instance, two minority teenagers were killed after a police chase in the Paris suburbs as they left a soccer game, triggering weeks of riots across France.

But this time, a local incident has intersected with an international current, translating “Black Lives Matter” into French and galvanizing a message increasingly global in its appeal.

[Sometimes it takes an outsider to crystallize America’s enduring racism]

This month, with the international spotlight on the Olympics in Rio de Janeiro, protesters have condemned the routine police killings of black civilians across Brazil. There have been similar demonstrations in Norway and Britain, where, last week, demonstrators invoking the Black Lives Matter message obstructed traffic into London’s Heathrow airport. In Canada recently, over 500 people marched in Ottawa to protest the death of a mentally ill black man after his arrest.

When about 600 protesters joined France’s first-ever Black Lives Matter demonstration in Paris four days after Adama’s death, they were taking part not only in what was couched as an international intervention against anti-blackness but also against what Fania Noël, 29, a founding member of the movement here, called France’s “Republican mythology.”

Born in Haiti, Noël moved to France at age 3 and grew up in a housing project in the distant Paris suburb of Cergy, not far from where Adama died last month. She described her family as the “nightmare of the French right”: low-income, immigrant and black.

“We never lived the illusion of integration,” she said.

For her, France’s “mythology” is largely the widespread assumption among the predominately white elites here that race is no longer applicable in a country that was once a major slave trader and the seat of an empire that spanned much of North and West Africa, North America, Southeast Asia and the Caribbean.

The French government’s rationale for not officially recognizing race largely stems from the still-bitter memories of World War II, when the country’s government collaborated with Nazi Germany to single out French Jews on ethnic grounds. But critics of the policy today insist that banishing data on race did not banish racial discrimination.

“Race doesn’t exist — unless you need a job, an apartment, to get into school or if the police stop you,” Noël said.

Annette Davis, another organizer of Black Lives Matter in France, criticized what she sees as the more general problem of the French government’s refusal to accept that people of color can experience life differently.

“It’s essentially propaganda,” she said, referring to the French government’s particular definition of equality. “ ‘We are all human, colors do not matter, and secularism,’ but redefined in a really manipulative way: not having a religion, but really just not being too authentically Muslim.”

“There is this idea that we need to integrate ourselves, to assimilate and become as white as possible. Yet this is a country that colonized so much of the world, and there are so many black and brown faces in France. There’s a colonial past, but there’s also a colonial present.”

[Why some whites are waking up to racism]

On the specific question of police brutality, about two weeks before Adama’s death, France’s National Assembly had rejected an amendment to a bill that would have required police to issue a written record every time they stopped someone on the street — including the legal basis for that stop.

Advocates had hoped these records would provide a more accurate picture of suspected racial disparities that, at present, no data exist either to substantiate or disprove. For now, only the perception of police impunity lives on, a perception that cannot be challenged in any court.

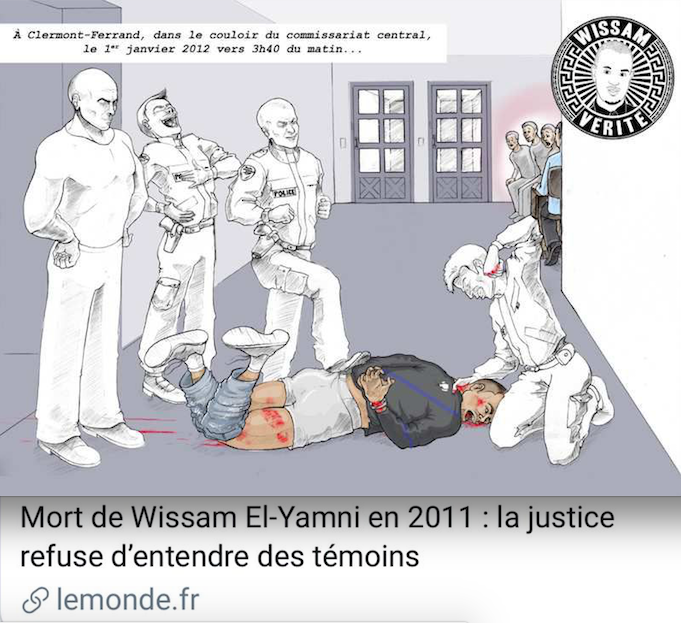

In January 2012, Wissam El-Yamni, 30, died after nine days in a coma that followed his arrest early in the morning of New Year’s Day.

For his brother, Farid, 30, an engineer, what matters most is that, as in the case of Adama Traoré, police officials never provided accurate information at any point in the days that followed, blaming his death on medical problems that could not later be verified.

“When the authorities lie, they’re saying that we don’t merit truth, and that we don’t matter,” he said in an interview. “You say, ‘I exist.’ But they say, ‘You don’t exist — you’ve never existed, in fact.’ ”

Farid said that he worries France’s current political climate — an atmosphere of heightened national security after three major terrorist attacks in the past year and a half — could prevent any lasting change to the country’s policing culture.

“There’s the idea that fighting police violence is somehow being against security,” he said. “But they’re not contradictory.”

Despite what she described as the success of France’s first Black Lives Matter rally, Noël said that there has been little substantive engagement from either French government officials, public intellectuals or journalists in the same way that there was during the widespread protests triggered by a controversial labor law earlier this year.

“With ‘Nuit Debout,’ ” she said, using the French name for those protests, “even if they were criticized, they were still taken seriously — they’re still political subjects. We’re viewed as a band of barbarians, like colonial subjects, except this time of the interior.” A majority of the Nuit Debout protesters, she said, were white.

Most of the debate in French media on the Traoré cased has focused on the legal nature of police practices rather than on the question of structural racism.

In a cafe in Beaumont, Lassana Traoré said that, regardless of the publicity, his family still feels ignored, having received no official condolence or acknowledgment from the French government.

As a result, Lassana said, they have arranged for Adama’s body to be transferred to Mali, the country where their father was born.

“He died here in a manner far too complicated,” he said of his brother. “He can rest in peace in Africa.”

/image%2F1527421%2F20161022%2Fob_5f2a1f_graphic-affiche-noir.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fi.ytimg.com%2Fvi%2FoQwSIqmvF-U%2Fhqdefault.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fresistons.lautre.net%2Fsquelette-IMG%2FMENU-SOM-99x43.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fhuffpost-focus.sirius.press%2F2023%2F11%2F10%2F0%2F220%2F1333%2F750%2F1820%2F1023%2F75%2F0%2F8812850_1699626812593-1516897-jpg-r-1920-1080-f-jpg-q-x-xxyxx.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fcontre-attaque.net%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2023%2F11%2Fsignal-2023-11-08-090607_002.jpeg)